The surreal day I rocked up to Disney World with Charlie Watts: Rock biographer PHILIP NORMAN recalls his priceless personal memories of the legendary Rolling Stones drummer he knew for six decades

That winter of 1965, the Rolling Stones had just released Satisfaction, seemingly the most smutty single ever.

It wasn’t actually smutty at all — the most suggestive thing about it was the title — but they were at a peak of notoriety encouraged by their manager, Andrew Oldham, who realised that fans wanted something edgier than the family-friendly Beatles.

Soon afterwards they did a gig at the ABC Cinema in Stockton-on-Tees and that’s where I first met Charlie Watts, interviewing him and the rest of the band backstage as a cub reporter for a northern newspaper.

With the press depicting them as scruffy and dirty, I expected to be greeted by a bunch of grunting Neanderthals, but Charlie was the most hygienic, fragrant and well-dressed pop musician you could wish to meet.

The others were more wacky but even Brian Jones, the prototype rock star, washed his hair twice a day and they were all perfectly nice to me, even signing a page of my notebook.

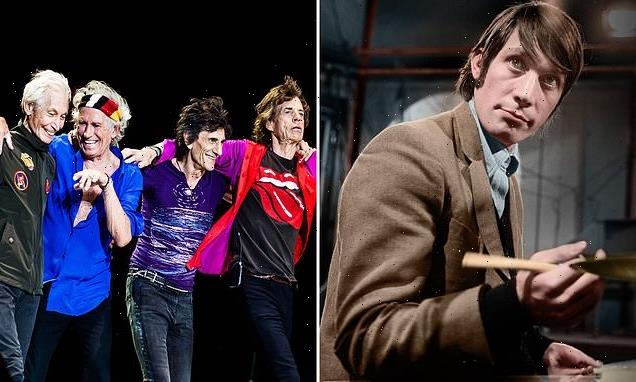

I first met Charlie Watts, interviewing him and the rest of the band backstage as a cub reporter for a northern newspaper, in 1965

When Charlie, a former art school student, added his name, he put a little decorative border around all the signatures, together with the name of the band in case I should forget who they were.

No one thought then that they would still be going even six months later, let alone more than 50 years.

Charlie, who was then 24, had not long given up a regular job working for an advertising agency, and he was still living with his parents in North London.

A girl I knew had been out with him some time earlier and told me how, every Friday night, he brought his mum home a coffee-and-walnut cake. He got one for this young woman as well, only he’d take the walnut off the top of her cake and put it on his mum’s so that she would have two.

By the time I met him he was married to Shirley Shepherd, a sculpture student at the Royal College of Art. They were together right up until his death and he famously attributed the success of their 57-year marriage to the fact that ‘I wasn’t really a rock star’.

Throughout his life he remained faithful to Shirley, once explaining that ‘on tour everybody is sleeping with everybody else but I have nobody to sleep with so I talk to people and draw’.

Once, when the Stones visited Hugh Hefner’s original Playboy Mansion in Chicago, he ignored all the orgies going on around him and just sat there sketching people, a little oasis of innocence amid all the depravity.

As for talking, I was one of the people he often fell into conversation with when I accompanied the Stones on various of their tours.

With the press depicting them as scruffy and dirty, I expected to be greeted by a bunch of grunting Neanderthals, but Charlie was the most hygienic, fragrant and well-dressed pop musician you could wish to meet. Pictured: Rolling Stones in 2018

In those days, before rock became industrialised and PRs hung around limiting you to half-hour interviews, you really could get to know the musicians, and Charlie made himself available far more than most.

It would take ages for the others to come out of their hotel suites each morning, but he would always be up early, prowling around in his knickerbockers or whatever stylish outfit he’d chosen for the day.

I knew that it was pointless trying to chat to him about the band because he was tired of people trying to get him to say something compromising.

Instead he loved talking about things like the American Civil War and The Buffalo Bill Wild West Annual, a 1950s children’s book we had loved as youngsters.

We both remembered the hero Wild Bill Hickok being shot in the back by ‘a two-bit gambler called Jack McCall’. Charlie told me how, as a little boy, he had carefully covered his copy of the annual in brown paper to keep it in pristine condition.

Apparently he did this with all his books, a telling detail which wouldn’t have made good newspaper copy at the time but told you everything you needed to know about how far he was from being ‘rock ’n’ roll.’

He really was the reluctant Rolling Stone. His first love was jazz and his publicist once told me that, wherever they were in the world, Charlie was always longing to catch the next flight home.

Neither did he have time for the politics within the Stones.

The others were more wacky but even Brian Jones, the prototype rock star, washed his hair twice a day and they were all perfectly nice to me, even signing a page of my notebook. Pictured: The Rolling Stones in 1968

They were worse than the Borgias, forever falling out with each other, but they all liked Charlie because he wasn’t a competitor and he wasn’t an attention-seeker.

In a world where everything is about image and facade and pretence, he was always resolutely himself. To have stayed so triumphantly not a Stone while in the Stones was pretty amazing, as was his lack of ego.

The length of some of their gigs meant that a chamber-pot had to be placed on the stage so that they did not have to go back to their dressing-rooms during shows. This was placed near Charlie’s drums and it can’t have been nice to have your band members relieving themselves out of sight of the audience but directly in your eye-line.

You can’t imagine big characters such as Ginger Baker and Keith Moon, drummers with Cream and The Who, putting up with that, but it was typical of Charlie that he did.

Hearing of his death, after all these years with the Stones, it’s as if one of the great stone images of the American presidents has been removed from Mount Rushmore.

And that’s an appropriate image because Charlie really did have a stone face, seeming to me like a rock and roll version of Buster Keaton, the unsmiling silent film comedian. His humour was so dry that you really had to be tuned into it, but there was something ironic about his whole manner which suggested that he never really took things seriously.

On one of their tours, the Stones played in Orlando, Florida, and I accompanied them around Disney World, where the attractions included a Wild West ride.

By the time I met Charlie (pictured in 1968) he was married to Shirley Shepherd, a sculpture student at the Royal College of Art

You would have thought that was right up Charlie’s street, but as always it was hard to tell whether he was enjoying himself or not. That said, he wasn’t always so impassive.

When news came through that Brian Jones had been found dead in his swimming pool in 1969 after being fired from the band that he had started and even named, Charlie could not stop crying.

When he did finally reach the limits of his tolerance, it was in typically Charlie fashion. Wild Bill Hickok himself would have been proud of the way he handled that incident in 1984 when he famously punched Mick Jagger for calling him ‘my drummer’.

What most accounts of that contretemps miss out is that Charlie stormed out of the room, leaving a shaken Mick Jagger trying to make sense of what happened and suggesting he would soon be back to apologise.

Sure enough, Charlie did reappear, but only to wallop Mick again: ‘Just so you don’t forget’.

That came at a difficult time in Charlie’s life. As has been reported in many obituaries, there was a two-year period when, with the future of the band in question and family problems including his daughter Seraphina being expelled from school for smoking dope, he began hitting the bottle and developed a heroin habit.

I was surprised by this. Many musicians are slightly needy and empty people for whom drink and drugs fill the gaps in their lives when they are not on stage, but Charlie always seemed very self-sufficient.

Wild Bill Hickok himself would have been proud of the way he handled that incident in 1984 when he famously punched Mick Jagger for calling him ‘my drummer’ (pictured together in 2014)

There was plenty going on for him at the estate in Devon where Shirley bred Arabian horses and he collected vintage cars. This perhaps explains why his lost period was relatively brief, lasting only two years, before a fall down his cellar stairs when he was fetching a bottle of wine resulted in a broken ankle and a realisation of all that he was in danger of losing, his marriage included.

In the farming community of which he became part, he was a highly regarded and much-respected local figure, supporting the local hunt with generous cheques, and known in his local pub, the Duke of York in the village of Iddesleigh, as the ‘Drummer Boy’.

Of course, life was not without challenges, including his successful treatment for throat cancer in 2004.

Earlier this month it was announced that because of surgery for an unspecified illness he wouldn’t be joining the Stones on their forthcoming 13-date tour of the U.S.

His death, like his life, was far from rock ’n’ roll. Dying peacefully in a London hospital, he was surrounded by his family — a cherished husband, father and grandfather, one of the greatest drummers of his generation.

And still the kind and courteous man who drew in my notebook all those years ago.

Source: Read Full Article