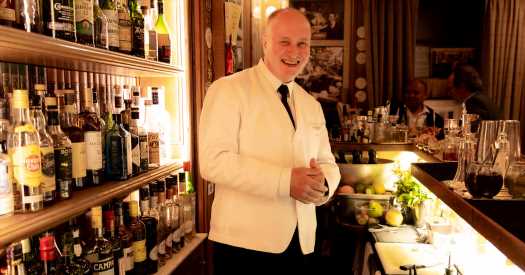

For nearly 30 years, the Bar Hemingway, a 34-seat, oak-paneled hideaway in the Ritz Paris, has been a destination for discerning Parisians and hotel guests in search of a perfect drink prepared by Colin Field, a jovial Briton regarded as one of the world’s greatest bartenders.

That came to an end quietly on May 15, when, two days shy of his 62nd birthday, Mr. Field served his last drink at the Hemingway. Habitués are bereft.

“Everyone asks me what should be on their itinerary in Paris, and I always say, ‘You can’t miss Colin at the Hemingway Bar,’” said Charles H. Rivkin, a former ambassador to France under President Barack Obama. For Mr. Rivkin and his wife, Susan Tolson, who would often walk over from the ambassador’s residence on the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré for a nightcap, Mr. Field created the Rivkin Martini, with Sorrento-lemon-infused vodka, shaken with ice in one of two shakers designed by Mr. Field, and served in a glass frozen at minus 23 Celsius (9 below, in Fahrenheit).

The supermodel Kate Moss, who has been going to the bar since the mid-1990s, said Mr. Field “makes just the right amount of fuss over you to make you feel special, and like you’re the only customer in the room.”

She was the inspiration for another Field invention, the Kate 76 (vodka, grapefruit juice and Champagne). Mr. Field tended Ms. Moss’s wedding to the British rocker Jamie Hince in 2011, and Ms. Moss wrote the preface for Mr. Field’s book, “The Ritz Paris: Mixing Drinks, a Simple Story.” In it, she described Mr. Field as “a four-part combination of gallant host, fairy godfather, conceptual artist and spiritual guide.”

“I will miss him and his stories,” she said in a recent interview.

Anya Firestone, a New York-born art specialist and guide in Paris who met her husband at the Hemingway, likened Mr. Field to the olive juice ice cube in the Clean Dirty Martini, a cocktail that took him 10 years to develop — “part of the experience,” she said, during an interview at the bar. She pointed wistfully to the cloudy hexahedron melting slowly in her cold vodka. “The Hemingway Bar is like a small town, and Colin is the mayor. I can’t imagine the place without him.”

As Mr. Field served a clutch of Clean Dirties and a Hemingway Daiquiri — double white rum, grapefruit juice and a drop of Maraschino — to a table of regulars a few evenings before his last call, he said: “I love the Ritz, and the Ritz loves me.” The ladies’ drinks, per usual, had a rose, pierced with a toothpick, attached to the glass rim like a brooch. “It’s been a beautiful experience. But it’s time for me to move on.”

Mr. Field hesitated to disclose the names of his famous customers. “As a bartender, I should respect their privacy,” he said. But he allowed that he has served a host of celebrities, journalists, authors, fashion designers, “captains of the U.S.S. Enterprise,” “several of the Batmans” and “all the James Bonds.”

“Pierce Brosnan would come on his own and say, ‘What should I drink?’” Mr. Field recalled. “‘Perhaps a dry martini, sir,’ I’d say, and I would make him the most perfect dry martini. In my own little head, I had served James Bond.”

Mr. Field decided he wanted to be a barman during a school trip to Paris as a teenager. He was enchanted by the city’s distinguished cafe waiters; to him, they represented romance and freedom.

When he returned home to Rugby, England, he set up a bar in his bedroom, with stools, glassware, bottles, the works. At 18, he wrote to the Ritz for a job. “They sent a lovely letter back that read, ‘Once you have done hotel school, please don’t hesitate to contact us,’” he said. He saved his money to attend the Ferrandi hotel school on the Left Bank of Paris.

Upon completion, he applied to the Ritz again but was told he was not yet up to its standards. He then worked for chic restaurants and bars across the city, including L’Hôtel, the 18th-century establishment in the Latin Quarter where Oscar Wilde died in 1900. It was there, in the “dungeonlike basement bar,” Mr. Field said, that he first met Ms. Moss, with Johnny Depp, her boyfriend at the time. Though Mr. Field was content with his work, the Ritz still pulled at him.

Understandably so: From the moment the Swiss hotelier César Ritz opened the Ritz on the Place Vendôme in 1898, it has been regarded as the ne plus ultra of hospitality. “At the Ritz, nobody jostles you,” wrote Marcel Proust, who made it his second home as he worked on his masterpiece, “In Search of Lost Time.” In 1921, the hotel added Ritz Bar in the Cambon wing, across the street from Chanel. For men only, the Ritz Bar was where Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald famously drank their way through the Roaring Twenties.

A small salon across the hall from the Ritz Bar opened in 1926, for women to wait as their husbands imbibed. It was known as the Steam Room, “because the ladies were steamed,” Mr. Field said. In the 1930s, the Ritz Bar started welcoming women, and the Steam Room was outfitted with a bar and rechristened Le Petit Bar.

After its charismatic bartender Bernard Azimont, who went by Bertin, retired in 1974 after 48 years of service, Le Petit Bar’s popularity declined swiftly. The Egyptian businessman Mohamed al-Fayed bought the Ritz in 1979. To revive Le Petit Bar, he renamed it the Bar Hemingway, at the suggestion of Claude Décobert, head of the hotel’s Bar Cambon.

To promote the bar, Mr. Field said, Mr. al-Fayed invited the whole Hemingway family over. But the rebranding didn’t take; it closed in the mid-1980s, and became a banquet storage space.

In 1994, Mr. al-Fayed wanted to try again. Mr. Field, who by then was an award-winning bartender, had interviewed for a position at the hotel’s Bar Vendôme two years earlier, without success.

But the interviewer remembered that Mr. Field was a literary sort and thought he might be a good fit for the Bar Hemingway. The hotel tracked him down and offered him the job. He opened the doors on Aug. 25, the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Paris after four years of German occupation — as well as Hemingway’s own “liberation” of the Ritz.

It was tough going at first. “I was on my own, and, before cellphones, people would receive calls at the bar,” he said. “There I was, trying to make a cocktail, give the bill, and answer and hand over the telephone all at the same time. That’s why I started serving water with a slice of cucumber as soon as customers sat down: because I couldn’t get to them for 10 minutes, and cucumber calms you down, and puts you in a receptive mood.”

With the success of the Hemingway, Mr. Field was able to hire additional staff; one of his assistants, Anne-Sophie Prestail, brought on in 2006, is now taking over as head bartender.

Over the years, Mr. Field decorated the place with Hemingway-themed memorabilia that he said he bought with his gratuities, like shark jaws, taxidermy and a model of Mr. Hemingway’s fishing boat, Pilar, as well as items from customers, including business cards, invitations and signed books.

Ms. Moss gave Mr. Field several antique manual typewriters, which sit on corner tables and the bar. For a while, he invited regulars to write letters, which they could leave for other regulars or have sent from the Ritz. He called it the Drop Dead Letter Club. “I would serve the martini on a silver tray, and say, ‘I have letters for you,’ and they would read their letters as they had their martini,” he said. “But then it got out of hand, and we stopped it.”

Though Mr. Field has left the Hemingway, he will not be idle. Private requests are pouring in, he said, such as a party on June 5 at the Palais Galliera, a fashion museum in Paris, where he plans to serve Curaçao-blue cocktails topped with meringues in cloud-etched glasses by the designer Jonathan Hansen. And in the fall, Mr. Field will return to hotel bartending, two nights a week at the Maison Proust, a new belle epoque-style boutique hotel in the Marais.

“Time to clear the tables and start again,” he said. “James Bond isn’t the only one who lives twice.”

Source: Read Full Article