When Britain’s Astronomer Royal puts out a short, easy-to-read book with the provocative title If Science is to Save Us, it behoves us to pay attention. By “us” I mean policymakers and commentators especially, but also all of us who can vote, for there’s no doubt about the mess we’re in. Martin Rees discusses the problems in all their awful solemnity: climate change, pandemics, cyber insecurity, the threat of bioterrorism and the potential for AI and bioengineering to run amok.

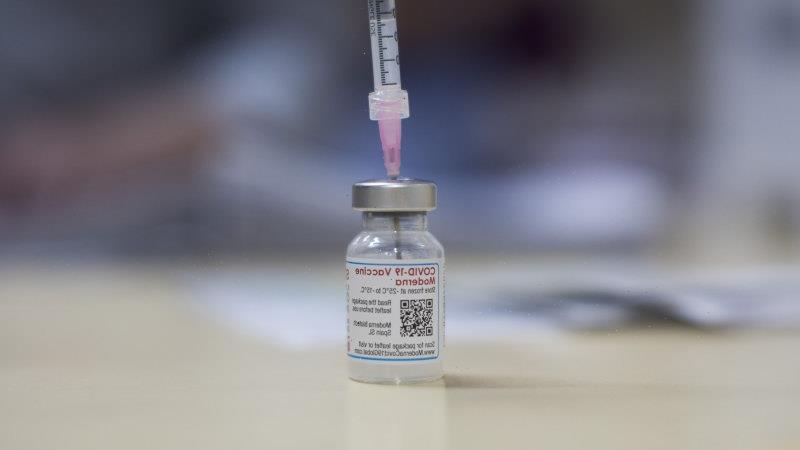

It’s also pretty clear that science will do most of the heavy lifting in averting or mitigating these potential disasters. The international effort to make new vaccines to combat COVID-19 is an obvious example. But Rees doesn’t shy away from the role science has played in creating some of our problems, and his key message is that we all need to contribute to the “informed public debate” needed for the ethical management and direction of science.

The work on a COVID-19 vaccine is only one example of how science can mitigate against potential disaster.Credit:Bloomberg

As he says, though, if this debate is to rise above “tabloid slogans”, we all need a “feel” for science. His approach is interesting, and somewhat surprising. Instead of explaining some of the crucial science we need to have a feel for, or showing in any detail its marvellous creativity, he aims to take readers into the sober, day-to-day reality of science.

He begins with a brief overview of today’s “transformative” scientific topics, and outlines related ethical dilemmas, such as who should benefit from costly biomedical treatments, and how much our climate strategy should take account of future generations compared with living ones.

He proposes dozens of creative solutions – encouraging innovation via more flexible career options; a rethink of scientific funding and accreditation metrics; and using foreign aid to establish Centres of Excellence in the developing world, to name only three. He also discusses why nations “may need to cede more sovereignty” to international regulators, and why it’s time governments were better prepared for potential disasters and disruption.

There’s an urgent need, he says, to “rebalance the trade-off between resilience and efficiency” – to abandon “just in time” strategies such as global supply chains, and to adopt a “just in case” approach.

Astrophysicist Martin Rees proposes dozens of creative solutions to the problems facing us.Credit:Getty Images

But effective solutions and controls need the support of the people, and so Rees invites readers to “Meet the Scientists” to find out what they do – and also what they cannot do. Part of the feel for science, he says, is “a feel for how much confidence can be placed in science’s claims”. So, he explains the unfolding, provisional nature of science, the problem of reductionism, and the way science is symbiotically linked with technology.

“If we don’t get smarter, we’ll get poorer,” he suggests, pointing out that the institutions that foster and support science need an overhaul. This includes our education system, where he supports STEAM rather than just STEM: the A is for Arts, which help equip students to make the ethical and political decisions needed in implementing the best and most useful science.

Rees’ decision to emphasise problems and policy makes for important, if not exactly riveting, reading. Much of what he offers is not new, for Rees himself is one of those who’ve been saying similar things for years – at least since 2003, he notes, in his book Our Final Century. Which says much about our collective failure to grasp the urgency.

Some of his suggestions are controversial, of course. For example, he supports research into safer nuclear energy. He’s also excited about the potential of scientific blogs and wikis for “democratising” involvement in scientific research, and in communicating and even refereeing it, but he doesn’t explore the problems already associated with the internet. And while writers such as Karen Armstrong (Sacred Nature) suggest science cannot save us if we are disengaged from nature, Rees prefers not to be “nostalgic” about what we’ve lost – such as city children never seeing a dark night sky or a bird’s nest – emphasising the wonder that can still be nourished by scientific documentaries and experiments. Indigenous thinkers, by contrast, have long warned of the dangers of disconnection from Country.

But analysis is not Rees’s intention: his is a broad brush, a wide-ranging discussion paper enlivened by insights from his own experiences. These include his membership of influential scientific bodies, from the Royal Society to a 2021 “special inquiry” into “risk assessment and risk planning”, and he gives a terrific insight into the role such committees can play in advising governments.

Even if the potential for climate and tech-induced catastrophe is small, the stakes are so high that if we can reduce the probability of disaster “even by one part in 1000, we’ll have more than earned our keep”. He’s speaking of scientists here, but it’s also an inclusive “we”, for it’s up to all of us to understand the problems and support the best solutions. Rees offers a rallying cry and a road map, hoping readers will engage sufficiently with science to ensure that it does, indeed, save us.

If Science Is To Save Us by Martin Rees is published by Polity Press, $41.95.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article