My first ever book club had only two members: me and my mom. Aside from our routine Sunday afternoon visits to our local library, there wasn’t any real formality or structure to our meetings. But I cherished that quality time, carefully browsing book spines in search of our next selection.

Talking about romance books with my mom sparked some of the realest conversations we’ve ever had.

I continued reading these novels well into my teenage years, but still wasn’t completely sold on the genre. Well, my issue wasn’t with the genre itself, more so with the lack of diversity in most of the stories. Years of reading about mostly white, blue-eyed characters gave me the impression that the writers and book industry gatekeepers didn’t care enough about people like me (a young Black woman) or my mom (a grown Black woman) to write and publish romances that included and spoke to us.

Every now and then, I did discover a few novels that centered the romantic lives of Black girls and women, 90s cult classics like Omar Tyree’s Flyy Girls and Sister Soulah’s The Coldest Winter Ever were passed around like hotcakes at my school. While I recognized and related better to these characters, these books represented only a slight portion of the wider spectrum of Blackness. And so my hunt for nuanced representation in romance continued into adulthood. What I didn’t realize was that I was searching for a book that didn’t yet exist.

In college, I got an on-campus job at the Howard University Bookstore. That’s when I learned more about the inner workings of the book industry and realized I could spin my literary aspirations into an actual career. So for the past decade, I’ve worked as a marketer at some of the top publishing houses, helping to introduce and uplift Black authors and their books to a national audience.

When I first got into the business, I tried to pinpoint the first young adult romance novel written by a Black author, expecting to find an underrated book written long ago. What I found shocked me. The book that kept popping up in my search was Indigo Summer by Monica McKayhan, a 2017 novel published by Kimani Tru, the first ever imprint or division created for Black young adult romance books. (Interestingly enough, McKayhan revealed in a 2009 interview that her motivations were just like mine: “I first had the desire to write for young people when I discovered that teens were reading their parents books (inappropriate adult books),” she said “There was clearly a lack of stories for young people of color.”) My publishing job was fulfilling, yet things weren’t changing fast enough. By 2018, six years into my career, romance books penned by white authors made up 90% or more of most publishers’ offerings.

So by day, I kept advocating for Black authors and, by night, started down the path to become one.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CejKi6PrXzI/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading

A post shared by ebony (@ebonyladelle)

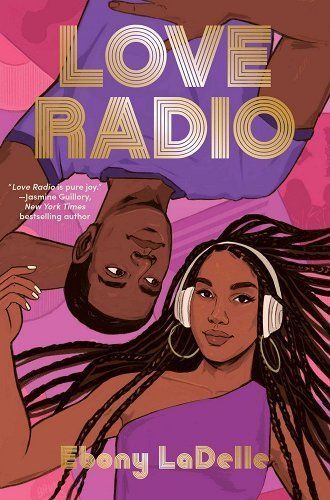

Throughout 2019, I dreamed up the kaleidoscopic lives of Prince, a Detroit-based DJ and resident love expert, and Dani, the cynical aspiring writer who also happens to be Prince’s childhood crush. Inspired by Jasmine Guillory, Nicola Yoon, Kristina Forest and other trailblazing Black women romance authors, I wrote Love Radio, a story that I felt 13-year-old me would read, one that spoke to my individual and communal experiences as a Black girl without hyperfocusing on stereotypical images of inner-city communities. And once 2020 hit and I began noticing how Black communities were hit hardest by and during the coronavirus pandemic, writing about love was a balm of joy in a time of hurt and devastation.

There’s still a long way to go. Achieving real change in romance literature requires supporting both the Black authors who are already bodying this genre and upcoming and debut authors alike, while challenging the status quo of what romance should and can look like. That’s why I’m thankful for those book club days with my mom, when I learned to consider different types of stories and question the vast gaps of representation. I learned the power of honest and insightful criticism, the significance of writing as a craft. I hope we continue to witness more and more authors from marginalized communities, writing about the love stories they didn’t see for themselves growing up. And for all the future generations of teens, it’s my wish that they never feel a lack of representation, or love, again.

Source: Read Full Article