The rigorously restrained, contemplative nature that struck viewers of Christopher Makoto Yogi’s first feature, August at Akiko’s, in 2018, remains the distinctive trait of his new film I Was a Simple Man. At its core an account of an aging man as he willingly takes the dive from being into nothingness, the film is defined by its discipline and a style that might be called lushly austere. This is refined, specialist cinema that will be warmly embraced by aesthetes.

The film premiered Friday in the Sundance Film Festival’s U.S. Dramatic Competition lineup.

Yogi’s cinema is built on blocks of strong, mostly static compositions and a mood in which the serene beauty of the Hawaiian setting is encroached upon by restless winds, insistent music, relentless Westernization and unsettling portents of mortality. Calm acceptance of the inevitable does quiet battle with clenched fear and the ever-growing specter of morality. We all know how it ends, but you can define yourself by how you ride it out.

Yogi refrains from spelling out much of anything, so entering into the film is a matter of sorting things out for yourself; low-key barely begins to describe the dramatic tenor of narrative. The area around his home in northern Oahu seems essentially undisturbed by the gentrification of the state, and there is initially a feeling of abiding calm that allows the sights and sounds of threats to a serene existence become more pronounced than they otherwise might.

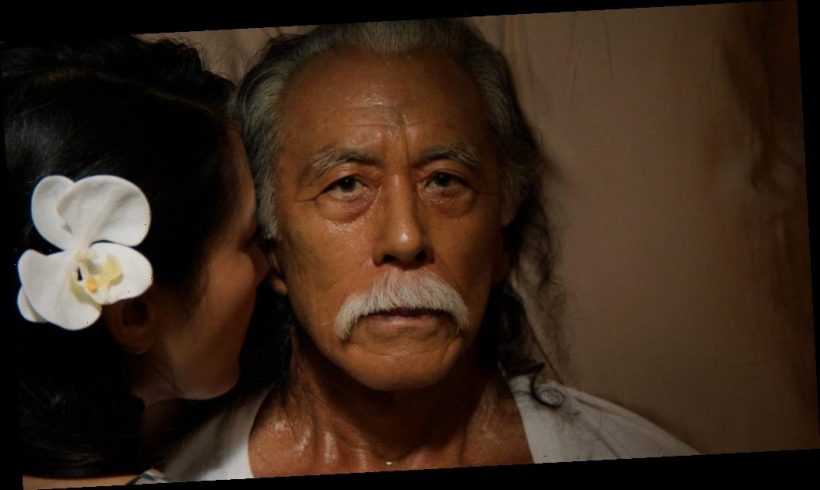

Masao (Steve Iwamoto) is a handsome gent with a ponytail and white moustache. A man of few words, he now does minimal chores at best. When he picks up his son, they speak of the latter’s late mother, who died young, and when family comes to celebrate a birthday, they stay all day. It’s a thoroughly uneventful event.

But while nothing in particular happens, the dominant mood is ominous. A full moon is accompanied by restless winds, water sounds and a general unease, a feeling compounded by Masao’s concerned and nervous manner. The ill portents soon become justified when doctors confirm that the man is seriously ailing, which causes him to withdraw almost entirely.

Assuming centerstage, then, are unannounced “visits” from key people in Masao’s past, going back as far as the man’s idyllic youth in pre-statehood days. Wistfulness bleeding into sorrow dominates the man’s head and heart, as Yogi drops Masao into assorted moments and memories of his past with his wife, whose death at a very young age served to also distance himself from his kids.

Although Yogi is too rigorous a filmmaker to indulge in anything resembling conventional nostalgia, he can’t restrain himself from conveying an implicit distaste for the relentless Americanization of the islands. As the film revisits moments from the family’s past going back decades, there is more than a whiff of time past and paradise lost; the photographic emphasis on skyscrapers and other modern artifacts is not accidental.

Somewhat unsettling and perhaps not sufficiently addressed is Masao’s long separation from his own family; perhaps understandably irascible in old age, he’s a man who largely checked out on his own family years earlier. There has to be a lot more to this story than we see in the film, and yet we only get crumbs when it comes to addressing anything like the full story. One provocative peek is an interesting painting of the father produced by his daughter while on death watch.

The drama doesn’t reveal itself in a normal fashion and finds its own way, more often with success than not, of giving weight to everyday—and sometimes borderline dull—events. In this regard, he’s following the lead of some of his preferred Asian art house directors—Naomi Kawase, Tsai Ming-liang and Apitchatpong Weerasethakul—whose slow and studied styles are antithetical to Western commercial filmmaking norms (Yogi’s two films thus far are on the short side). He also uses weather and music to indicate the brutal turbulence of what’s going on beneath the characters’ mostly reasonable exteriors.

Yogi’s style and concerns as expressed here remain rigorously aestheticized for a very particular public, but there are hints of an opening up to a wider viewership. The director is in full command of what he’s doing, so he will be worth following to see if he’s content to remain a figure of specialist interest or tries to expand his palette and audience.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article