He was inescapable – his smiling face everywhere: on every street, in every supermarket, on every screen.

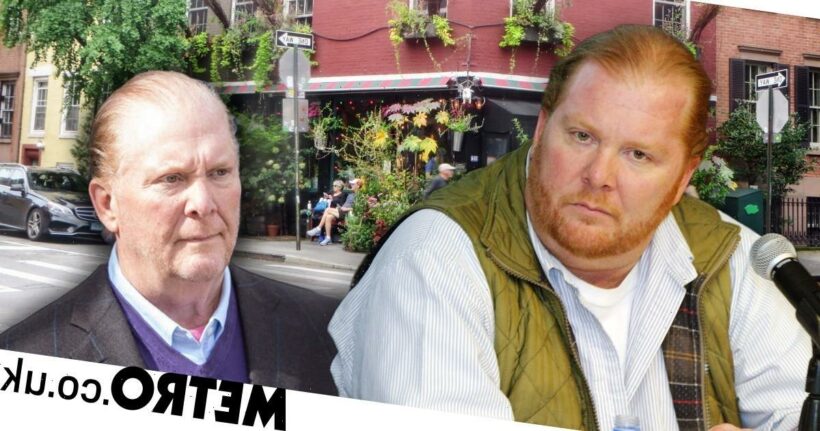

Mario Batali was a household name and ‘visionary’ in America thanks to his unique and tasty takes on traditional Italian cuisine. As well as fronting numerous shows for the Food Network, and appearing on primetime cooking programmes Iron Chef and The Chew alongside his own range of supermarket Italian staples, Batali was the proud owner of 26 restaurants across the globe, in addition to serving as a consultant and investor in numerous others.

One of his more notable investments was in New York City’s hotspot The Spotted Pig – a late night burger joint frequented by the A-List; regulars included Beyonce, Kim Cattrall and Keanu Reeves.

But lurking beneath the $250million food empire Batali fronted were the scores of women who had helped him build it, left violated and ashamed after Batali allegedly sexually harassed and abused them – something he has vehemently denied.

Now, the story of these women, who took on Batali in 2017 as the #MeToo movement gained traction, is being told for the first time in Discovery+’s Batali: Fall of a Superstar Chef.

Batali isn’t the typically suave chef usually associated with the upper echelons of New York’s culinary scene. Stout, with a flushed face, the 62-year-old is instantly recognisable for his signature long ginger hair, usually scraped back into a low ponytail.

Outside of his crisp, clean chef whites, Batali favours brash, mismatched clothes, which he always paired with his bright orange Crocs.

But what endeared him to others was his loud, vibrant and cheerful personality, which immediately drew people in and made him well-liked and respected. Batali had a rare knack of being instantly popular to those around him – and so, when the chef particularly reciprocated feelings of friendship, ‘it made you feel special,’ a former colleague explains in the documentary.

His natural magnetism was complemented by his genuine talent. Having been a sous chef at the Four Seasons in San Francisco aged just 29, Batali travelled Italy to perfect his craft before reaching out to friend Steve Crane to team up and open their first restaurant, Po, together in 1993.

The intimate Italian diner received a rave review from the New York Times, which saw Batali catapulted into mainstream success, garnering numerous cooking books and TV endorsement that enabled a meteoric rise to the top.

It was this status as a star that led to the feeling Batali was entitled to do whatever he liked, the documentary’s director, Signeli Agnew, tells Metro.co.uk.

‘He was larger than life,’ she explains. ‘We try to show how the world of celebrity can overshadow and enable. It was a free pass for him. It allowed him to get away with things that he may not have been allowed to otherwise.’

After finding fairly fast success on the New York dining scene, and juggling his fledgling media career and expanding empire, it was at The Spotted Pig where Batali let his hair down.

The pub-turned-diner differed from other white-tableclothed restaurants in Batali’s oeuvre: it was a cosy, darkly lit venue, adorned with plenty of nooks and alcoves for privacy, resembling more of a den of iniquity than a top eatery. It was the venue for the ‘after’ after party, where anything goes.

The venue’s third floor was where most of The Spotted Pig’s partying took place, with former server, Trish Nelson, tasked with having to look after guests up there – away from the prying eyes of the general public.

‘It was like a weird studio apartment,’ she recalls. ‘And there were no limitations. You want to smoke pot? Great, there’s some pot behind a petunia plant.

‘We’d find vials of cocaine in the banquettes when we were cleaning.’

Sex and topless dancing were also mainstays of the third floor, where discretion was essential for The Spotted Pig’s most illustrious diners. One server remembers seeing people tidy up around Batali, while he allegedly received oral sex from a guest.

Drinks were free-flowing when Batali came in to party, which, according to staff, was at least once a week.

‘When he was in, we knew we had to get two bottles of Averna, six bottles of his wine, loads of beers and packs of cigarettes,’ explains former general manager, Jamie Seet.

‘At the beginning of the night, he was just a normal guy, but the more he drank, the more sloppy and handsy he got.’

It was almost a joke amongst staff that you shouldn’t stand ‘too close’ to Batali, as he would allegedly routinely grab breasts or groins, or hug and kiss those around him without consent.

I honestly believed it was my responsibility to process and filter these abusive behaviours

In one incident, where Nelson was serving drinks to guests, she told the table she would ‘come back’ to bring more cocktails to them.

‘Batali replied: “If you sit on his face, he’ll make you come again and again and again,’” Nelson remembers.

‘In that moment, my body just dropped. He wasn’t my boss, but as a major investor with a lot of power, he could have got me fired at any point.’

Batali’s behaviour was so normalised, the women would refer to the chef as ‘the Red Menace’ or ‘Jabba the Hut’ among themselves when they knew he was in the restaurant.

While the staff who worked at The Spotted Pig knew what they had to endure on a regular basis was wrong, there was a culture of fear which prevented them from vocalising concerns.

Many of the young women who were working there on pitiful wages were trying to break into the New York creative scene, juggling acting, modelling or music with a job that paid their bills.

There were also the constant reminders that only a select few got to work at The Spotted Pig, and that they were ‘lucky’ they got to spend their evenings amongst such hallowed company.

‘This is not a corporate gig,’ Nelson explains. ‘You don’t get to have a say in how your work environment affects you personally.

‘I honestly believed it was my responsibility to process and filter these abusive behaviours. There were many shifts where I would go into the bathroom to have a quick cry before I pulled up my bootstraps, splashed water on my face, and walked back into the lion’s den. Oftentimes my tip money went directly to my therapist.

‘Wome are conditioned to believe that they are somehow responsible for negative behaviours that are present with heterosexual men for the sake of “likability” and the protection of career advancement.

‘It takes a long, long time to unwind this misogynistic ball of twine, and so most women stay silent for decades before they’re able to muster the strength and courage to speak out. It took me until I was 40 to openly begin to question some of these societal norms.’

Director Signeli Agnew adds that the fear of speaking out still lingered for some of the women she approached, as Batali’s influence was just so widespread.

‘I had dozens of conversations, and it took months to build trust,’ she explains. ‘I was struck by how afraid so many people were to speak, even though the allegations against Batali have been widely known for five years.’

And those who did speak out at the time found themselves penalised for doing so, as Jamie Seet discovered when she observed disturbing behaviour from Batali.

‘I was counting cash in the office from the servers in the office on the third floor,’ she recalls. ‘There was a party there, with Mario Batali. We had cameras all over the restaurant, and there was one on the third floor.

‘The party had died down to just a woman and Mario, and the woman was super drunk. On the security camera, we could see Mario touching this woman, who was passed out at this point, and her inner thigh.’

Seet acted quickly – she ran to Batali and asked how his wife was doing and how his kids were. A colleague woke up the unidentified woman and ensured she got a cab home safely.

As the incident was on camera, Seet decided to show The Spotted Pig’s owners, Ken Friedman and head chef April Bloomfield, to explain that Batali’s behaviour was way out of line and for them to speak to Batali privately.

‘Nothing happened,’ Seet claims. ‘We told the people who were in power and they shook it off as just another Mario incident. I’m telling the people I’m supposed to tell, and they don’t give a f***.

‘I’m ashamed I didn’t put my foot down, call the cops and tell Mario he’s a f***ing pig.’

As the years went by, many staff came and went at The Spotted Pig, and servers kept in touch. Batali’s behaviour may have slipped under the radar, remaining just as gossip between staff, if it wasn’t for the MeToo movement in 2017.

The term, which was coined by sexual assault survivor and activist Tarana Burke in 2006, became popularised following the exposure of numerous sexual abuse allegations against now-disgraced film producer Harvey Weinstein. Women started writing MeToo on social media only to show the widespread level of harassment and abuse they have been exposed to.

I’m ashamed I didn’t put my foot down, call the cops and tell Mario he’s a f***ing pig

The movement triggered New York Times food writers, Julia Moskin and Kim Severson, to do their own investigation into harassment in the food industry, with Moskin taking to Twitter to ask: ‘Who was the Harvey Weinstein at your restaurant?’

The tweet attracted a huge response – which was unsurprising, considering around 70% of women in the restaurant industry report to have been harassed while at work (this rises to 9/10 people working in hospitality in the UK).

‘There are a lot of Weinsteins in this industry,’ Moskin says, simply.

A former server at The Spotted Pig saw her tweet – and as many of the ex-staff had stayed in touch, was quick to add that there were numerous people had experienced appalling treatment when they worked there both at the hands of Batali, and owner Ken Friedman (Friedman issued an apology when the New York Times piece was published, but also claimed ‘some incidents were not as described.’)

As Moskin and Severson’s investigation at the New York Times continued, freelance journalist Irene Plagianos had also started to look into Batali’s demeanour at his other restaurants for the online food publication Eater.

When both investigations broke in late 2017, just a day apart from one another, Batali showed contrition for his actions.

While he denied allegations of sexual assault, the chef issued an apology that his behaviour was ‘deeply inappropriate.’

‘That behaviour was wrong, and there are no excuses,’ he said at the time. ‘I take full responsibility and am deeply sorry for any pain, humiliation, or discomfort I have caused to my peers, employees, customers, friends, and family.’

However, Batali caused outrage when he issued an apology on his website, which accompanied a recipe for cinnamon rolls.

‘I think he thought the allegations would go away,’ Agnew explains. ‘This is someone who had a public platform for years, is super beloved, and has an enormous empire but had been relatively isolated from repercussions for years. He thought it would blow over.’

It didn’t – and a star as high as Batali’s had an awful long way to plummet. His upcoming Molto Mario show with the Food Network was immediately cancelled, and he was kicked off The Chew. Meanwhile, his cookbooks and pasta sauces were pulled from sale, and numerous business partnerships were pulled. He was banned from even visiting his own premises.

The published reports also prompted an increasing number of women to speak out against Batali, with some of the accusations becoming more alarming. Eva DeVirgilis came forward to accuse Batali of a historic sexual assault in 2005, but never filed a police report.

One account did result in criminal proceedings against Batali, with Natali Tene alleging the chef groped her while they took a selfie together in 2017.

However, Tele was subjected to intense scrutiny by Batali’s defence lawyers, who were allowed an extraordinary amount of access to her phone.

‘Natali’s personal communications were searched without any distinction or any showing as to what was relevant to the case,’ says director of Women’s Equal Justice Project and former sex crimes prosecutor, Jane Manning.

‘Here we have a criminal case where the defendant receives the full benefit of the 4th Amendment’s restriction of searches, and the accuser, who has that same constitutional right, did not have that right protected by the justice process. There’s something really wrong about that.’

In the search, Batali’s lawyers found Tele had discussed a separate and entirely unrelated case where she had served as a juror, with a friend. In a shock twist of events, Tele was then facing criminal charges herself – which Manning has described as ‘outrageous.’

‘This sort of action Natali did was actually pretty common, but having a juror brought up on criminal charges is extraordinarily unusual,’ she explains. ‘We have a prosecutor’s office that chose to bend itself well beyond what would be standard practise in order to come down like a tonne of bricks on an accuser. That’s really warped.’

Batali was acquitted, and as of October 2022, no further criminal charges have been brought to him. He has since sold all his restaurant holdings and kept a low profile.

For the staff at The Spotted Pig, they received a small kernel of justice, after New York Attorney General Letitia James opened two investigations – one into Batali’s restaurant conglomerate, and a second focused entirely on The Spotted Pig, to pursue better rights for workers in New York state.

Eleven former employees at The Spotted Pig won a settlement of $240,000 plus a 10 year profit sharing arrangement – however, Friedman closed the restaurant just 20 days after the settlement was announced.

For Singeli, seeing people use their power and wealth to elude justice only exemplifies how far there is to go, and cites fear that recent events have seen further erosions of women’s rights and liberties.

‘There’s often a step forward than several steps back,’ she explains. ‘I think the case of Amber Heard and Johnny Depp and the attention it received may have scared women from speaking out against powerful men.

‘There’s a lot more that needs progress, and the legal system often lags behind. The women who did speak up in the press are doing a service for all who don’t feel as safe coming forward, and eventually the legal system will catch up.’

With women’s rights, we often see a step forward and then several steps back

Manning acknowledges there’s often bias not just in the law itself, but how it is applied.

‘The five years since the MeToo movement has mostly left the legal system untouched,’ she explains.

‘The criminal justice system needs reform when it comes to sexual assault because most of the laws in this area were written by men in an era where there was very little public awareness about sexual assault. Many of our laws still reflect that. But it’s the implementation of our laws that can be problematic. Some laws can be enforced with disproportionate severity, and the Batali case reflects this.

‘Law enforcement is utterly unequipped to investigate these crimes and we need that to change ASAP.’

Manning adds women who are brave enough to speak about their experiences need to be more adequately served by the law.

‘These women are heroes,’ she says. ‘They came forward at great personal risk to hold predators accountable. The vast majority of sexual assault victims who come forward do so to protect others and that is really inspiring.

‘Now, we need to build a system that is worthy of them.’

Metro.co.uk received no response to multiple attempts to contact Mario Batali for comment. He has previously apologised for inappropriate behaviour and denied abuse and assault.

Do you have a story you’d like to share? Get in touch by emailing [email protected]

Share your views in the comments below.

Source: Read Full Article