Sir Gerard Brennan, the former chief justice of the High Court, died in Sydney on Wednesday. He was 94.

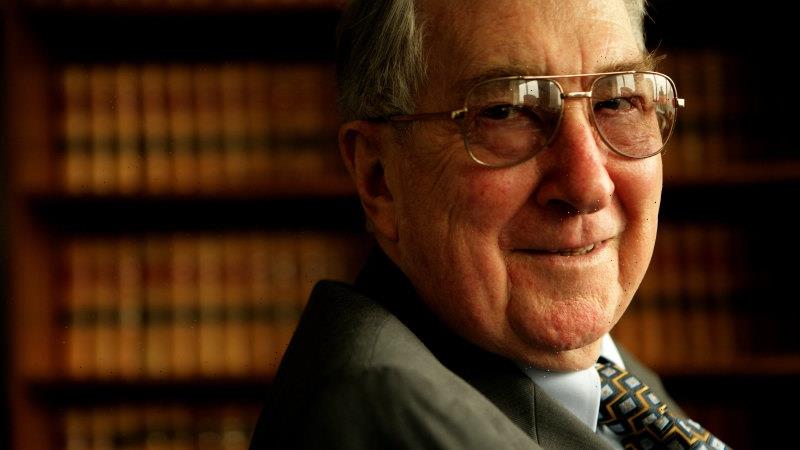

Sir Gerard Brennan of the High CourtCredit:Sahlan Hayes

Gerard Brennan, 1928 – 2022

Sir Gerard Brennan as a judge of the High Court of Australia in 1992 wrote the lead judgment in the case of Mabo vs Queensland, which abolished the notion of terra nullius and laid down forever the notion of prior Aboriginal occupation of Australian land. But for Brennan, it was hardly a spur of the moment decision. The ideas of fundamental human rights and justice, even when they overrode the formal dictates of statute law, had been embedded in him from youth when, as a devout Catholic, he was imbued with the notion of human rights. There could have been little more enforcement of that than the period in 1950 when, at 21 years of age, he became an associate to Justice Kenneth Townley who presided over the War Crimes Tribunal on Manus Island. Brennan could hardly have escaped the horrors of the brutality and excesses of power of the rampaging Japanese. But as Brennan came to realise, the excesses of the power of the state could manifest in many, more subtle ways. Brennan, who became Chief Justice of Australia in 1995, came to regard the judiciary as the guardians of human values.

Francis Gerard Brennan was born on May 22, 1928, in Rockhampton, Qld, the eldest of three children to Frank Tenison Brennan, a Labor Party politician, lawyer and judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland, and Gertrude (nee Koenig). He attended Christian Brothers Rockhampton and then Downlands College, Toowoomba, after which he entered Queensland University to study arts and law. His leadership qualities were quickly made evident. In 1949, he was elected president of the National Union of Australian University Students. His father died that year and the young Brennan, who had been an associate of his father, soon took the job with Justice Townley. Graduating, he was called to the Queensland Bar in 1951 and developed wide-ranging legal experience as a barrister in both criminal and civil law, renowned for his sharp intellect and pronounced social conscience.

Brennan married a medical graduate, Patricia O’Hara, in1953. Their first child, Frank, was born the following year, followed in rapid succession by Madeline, Anne, Thomas, Margaret, Paul, and their youngest child, Bernadette, born in 1962. In later years, when the family went to the beach, he would count the children and if he got to only six, would say: “Oh God, Trish, which one is missing?” None ever went missing. The demands of fatherhood hardly delayed his professional progress. A Queen’s Counsel from 1956, Brennan was briefed in 1973 to represent the Northern Land Council in the Woodward Royal Commission into Aboriginal Land Rights in the Northern Territory. The findings of the commission, largely based on the work done by Brennan and other lawyers representing Aboriginal interests, were relied upon by lawyers who drafted the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, the first attempt by an Australian government to legally recognise the Aboriginal system of land ownership and put into law the concept of inalienable freehold title.

Brennan was elected president of the Queensland Bar Association in 1974, a year later elected president of the Australian Bar Association, appointed in 1975 to the Australian Law Reform Commission, and was appointed in 1976 as a judge of the Australian Industrial Court and first President of the Commonwealth Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT). In the latter role, he demonstrated his commitment to fundamental concepts of justice, saying that the tribunal should exercise merits review of government decisions, that the tribunal should “not merely follow such government policies, but must first ask if it is lawful and then see that it does not produce injustice”. In 1977, the year he was appointed a foundation judge of the Federal Court, he said in a lecture: “Bureaucracies sometimes regard the AAT as an irksome trespasser on their territory – a cuckoo in the administrative nest. And so it is. And, in my respectful opinion, so it should be. It should also be a constructive participant in the improvement of administration and the refinement of policy.”

Brennan was appointed to the High Court bench in 1981, at a time when the court was deeply split and personal relations were stained. He played a key role as healer of rifts and worked hard to build a corporate spirit in the court. With many Northern Territory appeals to the court involving the interpretation of the novel Land Rights Act, he became even more familiar with the Aboriginal land rights issue. He recognised the spiritual relationship of Indigenous people to their land, and the importance of Aboriginal protection of their heritage, which he said in itself demonstrated prior Aboriginal occupation of the land. Quoting the anthropologist William Stanner, he said in a judgement: “No English words are good enough to give a sense of the links between an Aboriginal group and its homeland … The Aboriginal words would speak of ‘earth’ and use the word in a richly symbolic way to mean his ‘shoulder’ or his ‘side’. I have seen an Aboriginal embrace the land he walked on.” He lost none of his humility. Appointed a Knight Commander of the British Empire, he used some of his spare time doing the rounds for the St Vincent de Paul Society, in a part of Canberra where he was unlikely to be recognised.

Sir Gerard Brennan with his son Frank – the Jesuit priest, professor of human rights and Indigenous rights campaigner – after Frank received an honorary doctorate of law from UNSW in 2005.Credit:Peter Morris

After being appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) in 1988, Brennan reached what might be seen as his judicial zenith, in terms of impact, when he ruled on the Mabo case in 1992. He said: “No case can command unquestioning adherence if the rule it expresses seriously offends the values of justice and human rights (especially equality before the law) which are aspirations of the contemporary Australian legal system.” He rejected the legal view espoused over a century ago that Australia in 1788 was terra nullius. “There could be no worse human indignity to the first inhabitants of this continent to refuse to acknowledge their existence,” he said. Appointed Chief Justice of the High Court on April 21, 1985, he drew on his Christian commitments when he said that the person taking the oath would be “responsible not only to this court and this country but also his creator”. In his chambers was a portrait of Sir Thomas More, the 16th-century churchman who defied Henry VIII over the principles of marriage and divorce, More going to his execution stating that his ultimate allegiance was to God.

In Brennan’s view, the “black-letter law” principle as expounded by the then Chief Justice, Sir Garfield Barwick, was gone. He sought real justice that went beyond the formal lettering. It was stated in his citation for an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Queensland, that he had been “the supreme master of judicial creativity, the great exponent of the belief that judges are no mere passive recipients of law handed down by legislators but have themselves a significant role to play in the shaping of the law as well as the administration of law and justice. He has rejected the most formal and arid interpretations of the doctrine of separation of powers, on the principle that, where the legislature has been lacking or lagging behind, the judiciary has a proactive role to play.”

Sir Gerard Brennan in his office in 1995 after his appointment as chief justice of the High Court of Australia.Credit:Andrew Taylor

Retiring on May 21, 1998, he soon had a host of appointments, including foundation Scientia professor of law at the University of New South Wales, external judge of the Supreme Court of Fiji, chancellor of the University of Technology Sydney, and non-permanent judge of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal. He was awarded honorary degrees in New South Wales, Queensland, Ireland and by the Australian Catholic University, and became a life fellow of the Australian Academy of Law.

Brennan’s passion for social justice remained undimmed. At the launch of a Centre for Ethical Society in 2006, he said: “the social isolation of many Aboriginal people, or many refugees, of many who are poorly educated, and many who suffer from a mental illness, erodes their sense of self-worth and deprives them of hope. Yet like Levi passing on the other side of the road, we oftentimes seem to ignore the plight, or worse, regard them as a threat to our wellbeing. Our laws and policies do not reflect the Christian values of the Good Samaritan.” In 2021, he intervened in a public debate over a Sri Lankan family of asylum seekers, supporting the family with a letter in major newspapers “Are other Australians ashamed, as I am? How can Australia, proud of our freedoms, respectful of all our peoples, and insistent on human dignity, inflict cruelty on Australian children as a means of achieving a goal of government policy?”

Sir Gerard Brennan, whose wife died in 2019, is survived by his seven children – including son Father Frank Brennan, who became a prominent Jesuit, lawyer and strong social justice advocate, and two others who became QCs – 21 grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren.

Malcolm Brown

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article