AS the hull of the mighty vessel splintered and a torrent of freezing water gushed into the first-class cabin, bandsman Jock Hume did the unthinkable: he calmly retrieved his violin and played one final song.

For many of the 2224 passengers onboard, the last sound they heard was Jock's violin, the Titanic band's mournful hymn ringing out over the ocean.

Meanwhile, back in Dumfries, pregnant Mary Costin waited anxiously at home, praying that her fiancé Jock would be among the 700 survivors rescued by a passing cruise ship and heading for New York.

But ten days after the tragedy, on the day Jock and Mary were due to be married, there was still no update – although the crew of a recovery vessel had found a body in a musician's uniform bobbing among the Titanic's wreckage.

Weeks later, the letter which eventually arrived in Scotland bore terrible news: a body had been identified, and it was Jock's.

Mary was devastated, but she had closure, unlike the relatives of thousands of anonymous passengers whose bodies were consigned forever to a watery grave.

A desperate mission

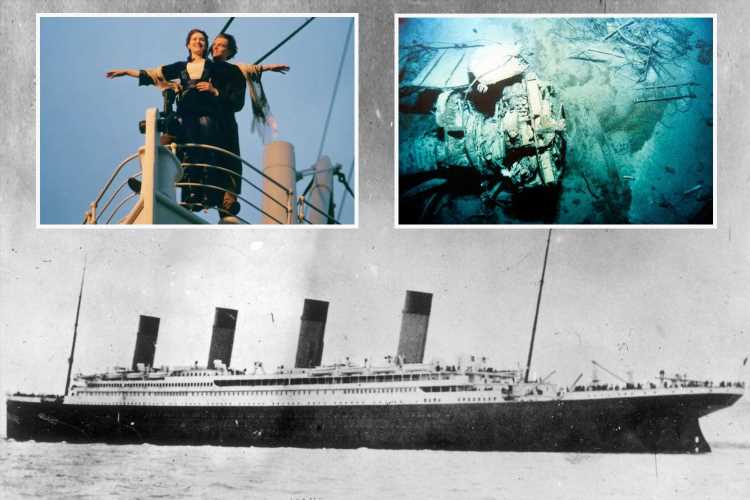

Everyone knows what happened when the "unsinkable" vessel, operated by the White Star Line, struck an iceberg on April 15 1912 – 109 years ago to the day.

But few people know the grisly story behind the recovery operation which prioritised first-class victims of the tragedy even in their death.

In the aftermath of the Titanic disaster, the CS Mackay-Bennett, a cable-laying ship docked in Canada was sent out in a recovery effort.

The vessel was based in the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, at the closest port to the Titanic's final destination, and so it was hired by the White Star Line to mount the official recovery mission.

With Captain Frederick H. Larnder at the helm, the hardy ship was stripped of its usual cables, loaded with coffins and turned into a "mobile morgue" complete with an on-board undertaker.

But leaving port on the 17th April, the crew of 75 – all paid double to compensate for the grim task ahead – never expected to find many bodies at the site of the disaster.

Titanic expert Christopher Ward, the grandson of Jock Hume, said in a Discovery documentary: "There were strong winds and currents carrying the bodies many, many miles.

"The White Star Line set it out with 103 coffins on board, so their expectations weren't high."

The dead and the debris

Built to navigate in ice and fog, the Mackay-Bennett braved choppy waters to reach the Titanic's last known position – arriving at the scene on Sunday 21 April, after four days at sea.

The crew found more bodies than they were prepared for floating among the driftwood, and spent seven days dragging corpses on-board, the hair of the dead stiff with cold and the eyelashes coated in frost.

Tracy Oost, a foresnsic anthropologist, says: "They would have seen frozen and frostbitten bodies. They probably wouldn't have looked in bad condition on the surface.

"But once they started pulling bodies out of the water they would have noticed that the [submerged] lower portion was far more decomposed.

"Most probably didn't drown. They would have frozen to death."

The bodies were hauled from the sea and laid out on deck, where they were numbered and their physical characteristics and records were noted.

The cruelty of the class system

After the first day of the week-long rescue mission, 51 bodies had been recovered, many too mangled or rotten to be identifiable if it wasn't for their belongings, which were meticulously logged and stored in numbered bags.

But soon the crew realised they had a problem: they were running out of coffins.

Before he set off, Captain Larnder had agreed a system to follow in case tough choices had to be made: bodies of first-class passengers, identifiable by the fancy clothes and expensive possessions, would be prioritised and given valuable coffin space.

The remains of second-class passengers, meanwhile, were stored in canvas sacks, while passengers identified as being third class would be buried at sea.

By the time the Mackay-Bennett was at full capacity, the ship was carrying 190 bodies – just over 10 per cent of all the Titanic dead – and 116 more had been cast back into the depths.

Of all the poor passengers who were left to rot beneath the waves, wrapped in cloth and weighed down so they would sink to the bottom, only 56 were ever identified.

Frederick Hamilton, the ship's engineer, wrote at the time: "The words 'we now commit this body to the deep' are repeated.

"At every interval comes a splash as the weighted body sinks into the sea. Splash. Splash. Splash."

Sacks soon ran out as well as coffins, and the Mackay-Bennett had to regroup with a support ship to collect more.

Before long, the ship was heavy with bodies – among them an unidentified male in the uniform of the Titanic band.

He was numbered 193 and brought back to land, where he would later be later identified as brave violinist Jock Hume.

The ship of death

The crew of the Mackay-Bennett had been told to keep an eye out for a particularly notable corpse – that of John Jacob Astor, the richest man on the Titanic.

His family had promised to give $10,000 (worth around £175,000 today) to whoever found his remains.

Astor was identified on-board the recovery ship thanks to his diamond cuff links and the initials embroidered in his jacket.

But nothing, not even finding the wealthy Mr Astor, struck the crew as much as finding the body of a little boy, around two years old, within the first hours of the rescue.

Even though there was no way to identify him, the crew couldn't bear to bury him at sea, so they stowed the body and brought it back to Halifax.

When the vessel, which had earned the nickname "the ship of death", came into view of the coastline, onlookers were stunned to see bodies heaped on the deck and the church bells in the town rang out in a grim chorus.

The dead were taken to the local curling rink – the only place big and cold enough to store them – where the local registrar set about identifying as many as possible based on their belongings and clothes.

A storm of fury

Up to this point, the White Star Line had refused to say how many people were missing, and would not reveal who had been presumed dead when asked by passengers' desperate relatives.

In Jock Hume's case, it took weeks before the violinist's death could be confirmed.

Meanwhile, the crew of the Mackay-Bennett had arrived home into a storm of fury about the water burials they had carried out.

But the men, determined to do the right thing, collected their reward money for finding John Astor and used it to hold a funeral for the unidentified boy they had found.

Many of them would come back to the cemetery every year to pay their respects to the child, whose tomb stone was marked "Our Babe".

Nearly a century later, in 2007, the mystery of the boy's identity was solved.

DNA tests revealed the corpse to be that of 19-month-old Sidney Leslie Goodwin, a third-class passenger from Melksham, Wiltshire, whose entire family perished on the Titanic.

In total, around 1,500 of the Titanic's passengers are still unaccounted for, with relatives of some victims still searching for clues today.

But even for families of the identified dead, there was a final slap in the face from the White Star Line, the company whose "unsinkable" vessel had sunk without enough lifeboats.

Staggeringly, the company charged families twenty pounds to have their loved ones' bodies returned to them – provided their relative hadn't been forever buried beneath the waters which killed them.

Source: Read Full Article