They take the knee, we live on our knees: Scathing words of a migrant worker in Qatar where hundreds have died building gleaming World Cup stadiums… yet the virtue-signalling England team remain silent

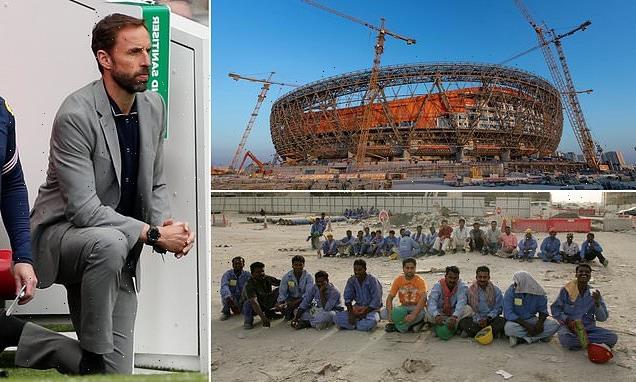

- Gareth Southgate’s men take the knee before every match to highlight racism

- But men from Africa, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh working for hours on World Cup stadiums, and died in their hundreds in conditions like a ‘toxic, dusty sauna’

- Indian migrant worker, 36, said: ‘They take the knee, but we live on our knees’

At any time of day or night, Qatar’s Lusail Stadium is something to behold. Drive north out of the capital Doha along a new five-lane superhighway, through a futurescape resembling the set of a Hollywood sci-fi movie, and it soon heaves into sight: a golden, fruit bowl-shaped edifice in the middle of the desert.

Illuminated at night, it is wondrous. But many Qataris believe the stadium, the venue for next year’s Fifa World Cup opening game and final, is at its best in late afternoon when the fading sunlight lends an ethereal dimension.

Not that aesthetics matter much to the army of low-wage migrant workers who helped to build it. Neither does its much-vaunted ‘advanced cooling technology’ which ensures the temperature on the pitch and in the stands is set at 21C (70F), when outside it is nearly 40C (104F).

What a tragedy, an obscene irony, too, say campaigners, that the labourers weren’t afforded the same consideration as players and fans. Or considered much at all, it seems.

For while this most modern of cooling systems was being installed – at the Lusail and in seven other stadiums – men from Africa, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh were working for hours on end on other World Cup projects nearby, and dying in their hundreds in conditions likened to a ‘toxic, dusty sauna’.

Gareth Southgate’s men take the knee before every match (pictured) to highlight racism but migrant workers building World Cup stadiums in Qatar have died in their hundreds and are treated as ‘staves’

Even now, ten years after the emirate won the rights to host the tournament, workers are still keeling over with fatal heat stress.

Nicholas McGeehan, director of human rights group Fair Square, says: ‘Employers took advantage of Qatar’s negligence and worked the workers to death.’

Racial discrimination plays a big part in their treatment. In a critical report last year – notably blunt in its use of language – the United Nations raised ‘serious concerns of structural racial discrimination against non-nationals’ in the emirate, which operates a ‘de facto caste system based on national origin’.

Non-payment of wages, unsafe working conditions, racial profiling by police and denial of access to some public spaces were among the abuses cited in the report.

With billions riding on the tournament, perhaps it’s not surprising that Fifa – football’s governing body, which raked in more than £4 billion from the 2018 World Cup – hasn’t exactly been vocal on the issue. Instead, says Mr McGeehan, it has been passive and unhelpful.

Our own Football Association, which stands to do nicely from the tournament, has also been quiet.

Mr McGeehan admits to being ‘a little disappointed’ with England manager Gareth Southgate’s response to the Qatar issue of late. Were Southgate to urge the FA to press for proper investigation into some of the manifest injustices in the emirate, it would make a massive difference, he says. Were the players to do so, the impact would be greater still. ‘It would be lovely if they [the players] would show everyone else the way on this,’ he adds.

A United Nations report last year cited non-payment of wages, unsafe working conditions, racial profiling by police and denial of access to some public spaces among the abuses Pictured: Lusail Stadium, the venue for next year’s Fifa World Cup opening game and final

They might wish to follow the example of Finland captain Tim Sparv, who last month wrote an impassioned article about Qatar on the The Players’ Tribune website, which gives sports stars a platform to connect with their fans. Sparv wrote: ‘I know that I might soon be playing in stadiums that have cost workers their lives.

‘We players are going to be the public face of a tournament over which we have no control. So I have wanted to know more – I have even spoken directly to migrant workers. And I can tell you this much: they appreciate and feel encouraged by the fact that someone is supporting and empowering them.’

Urging players across the world to speak out, he added: ‘Maybe some people will abuse you for raising your voice – perhaps they would either way. Maybe you will have some emails to reply to and some phone calls to answer. But when the history of this World Cup is written, you will be on the right side.’

In a symbolic gesture to highlight racism, Southgate’s men take the knee before every match, while striker Marcus Rashford has forced two Government U-turns on free school meals and spoken out against the cut to Universal Credit. Midfielder Raheem Sterling has campaigned on racial equality.

Near the Lusail last week, a small group of Indian workers, mostly drivers, were standing against a low wall as their long shift came to an end. It was early evening but still 38C (100F). Around them mechanical diggers zig-zagged across the scrubland outside the stadium, as yet unfinished.

One of the men, a 36-year-old father-of-two who arrived in Qatar from India five years ago, says: ‘I’m a cricket fan first, then football, but I hear what these [England] players do and it is a noble thing. But let’s remember that conditions here haven’t changed that much. They are appalling. We’re still little more than slaves.’

With a mirthless laugh, he adds: ‘They take the knee, but we live on our knees.’

He then scurries off, followed by his colleagues, all no doubt mindful of the dangers of exercising here what, in their own countries, would be an inalienable right.

There is the case of Malcolm Bidali, for instance. A Kenyan blogger and security guard in Qatar, he wrote under the pseudonym Noah about working and living conditions, of how his employers had no regard for welfare. Eventually Mr Bidali was unmasked as the mystery blogger, repeatedly interrogated, thrown into solitary confinement, given a huge fine and deported. ‘I thought I’d never make it out alive,’ he said.

One of the men, a 36-year-old father-of-two who arrived in Qatar from India five years ago, says: ‘We’re still little more than slaves… They take the knee, but we live on our knees.’ Pictured: Migrant workers in Doha

Nobody seems to know exactly how many migrants have died due to the intense heat and humidity in the past ten years.

According to a report by Amnesty, the tiny Gulf state has failed to investigate the deaths of thousands of workers, most of them in the prime of their lives. As many as 70 per cent are unexplained, a ‘damning statistic’ says Mr McGeehan, who adds that given Qatar’s well-resourced health system, it should be possible to identify the exact cause of death in all but one per cent of cases.

Invariably the Qatari authorities simply attribute them to ‘natural causes’ or vaguely defined cardiac failures. These classifications are meaningless without the underlying cause of death explained. As a consequence, it stops bereaved families getting compensation. ‘They’re simply putting bodies in coffins, writing down “natural death” and sending them home,’ says Mr McGeehan.

However the Gulf state has at least ditched (in theory at least) the medieval system that caused employees to be treated like serfs. This, says Mr McGeehan, is a welcome step and should be applauded.

Qatar has replaced the ‘kafala’ system – that forces foreign workers to seek their employer’s permission to change jobs or leave the country – with a new contract-based law. But Mr McGeehan says there has been a ‘clear absence of implementation’.

These and any future changes have, in any case, come too late for hundreds, if not thousands, of grieving families.

Men such as Bangladeshi Mohammad Kaochar Khan, a fit and healthy 34-year-old who died suddenly in a labour camp in Doha in November 2017 after working as a plasterer for three years, most recently for Redco Construction-Almana, a Doha-based firm. He left behind a widow and seven-year-old son who live in dire poverty in a rural district called Kishoreganj, around 60 miles north of the Bangladeshi capital Dhaka.

Like so many others, his horizons didn’t stretch much beyond saving to afford a bigger house back home, where he dutifully sent most of his wages, and possibly starting his own business.

Mr Khan’s younger brother, Didarul Islam, told The Mail on Sunday that too many workers had died for the World Cup to go ahead. ‘Such sports events will be a curse for those families who lost their loved ones,’ he said.

His family have heard nothing about compensation. Neither has Nazma Begum, 35, the widow of Bangladeshi worker Mohamed Hamidul Malita, 41, a carpenter who died after falling from a building in Doha in February 2019.

Like many other labourers, Mr Malita borrowed money from relatives to pay for the visa and flight, which cost him £3,000, when he left for Qatar in 2016.

Ms Begum, a housewife, said she now has to look after her 17-year-old daughter, 15-year-old son and her 65-year-old mother-in-law.

Struggling to make ends meet, she works as a casual farmhand to feed her family, as does her son, who is still at school.

Breaking into tears, Ms Begum said: ‘My husband’s body was brought back from Qatar and buried at home.

‘In his absence, I have been bearing the burden of this family. I am working in the paddy fields of others to feed my family.

‘We have lost the sole breadwinner in an accident in the Gulf’s richest country, which has done nothing to help us, no compensation. Every day is a day of hardship for us.’

Additional reporting by Owaisim Bhuyan

Source: Read Full Article