What is happening in Sudan, what is at stake for the West and how could the situation play out? Our Q&A explains all

- Fighting between two rival military factions has engulfed Sudan in warfare

- Both sides have tens of thousands of fighters, foreign backers and mineral riches

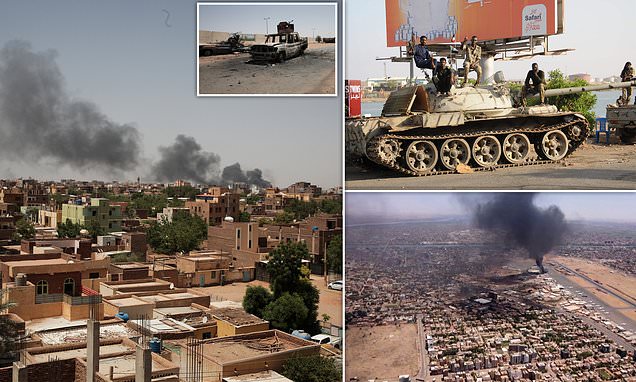

Fighting has erupted across Khartoum and at other sites in Sudan in a battle between two powerful rival military factions, engulfing the capital in warfare for the first time and raising the risk of a nationwide civil conflict.

The fighting between forces loyal to two top generals has put the nation at risk of collapse and could have consequences far beyond its borders.

Both sides have tens of thousands of fighters, foreign backers, mineral riches and other resources that could insulate them from sanctions. It’s a recipe for the kind of prolonged conflict that has devastated other countries in the Middle East and Africa, from Lebanon and Syria to Libya and Ethiopia.

The fighting, which began as Sudan attempted to transition to democracy, has already killed hundreds of people and left millions trapped in urban areas, sheltering from gunfire, explosions and looters.

Here, MailOnline takes a look at what is happening and the impact it could have on the rest of the world.

Smoke is seen in Khartoum, Sudan, on Saturday. The fighting in the capital between the Sudanese Army and Rapid Support Forces resumed after an internationally brokered cease-fire failed

WHAT TRIGGERED THE VIOLENCE?

Tension had been building for months between Sudan’s army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which together toppled a civilian government in an October 2021 coup.

The friction was brought to a head by an internationally backed plan to launch a new transition with civilian parties. A final deal was due to be signed earlier in April, on the fourth anniversary of the overthrow of long-ruling autocrat Omar al-Bashir in a popular uprising.

Both the army and the RSF were required to cede power under the plan and two issues proved particularly contentious: the timetable for the RSF to be integrated into the regular armed forces, and when the army would be formally placed under civilian oversight.

When fighting broke out on April 15, both sides blamed the other for provoking the violence. The army accused the RSF of illegal mobilisation in preceding days and the RSF, as it moved on key strategic sites in Khartoum, said the army had tried to seize full power in a plot with Bashir loyalists.

The fighting between forces loyal to two top generals has put the nation at risk of collapse and could have consequences far beyond its borders. Pictured: A battle-damaged street in Khartoum, Sudan

An aerial view of black smoke rising above the Khartoum International Airport on April 20 amid ongoing battles between the forces of two rival generals

WHO ARE THE MAIN PLAYERS ON THE GROUND?

The protagonists in the power struggle are General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the army and leader of Sudan’s ruling council since 2019, and his deputy on the council, RSF leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti.

It comes two years after they jointly carried out a military coup and derailed a transition to democracy that had begun after protesters in 2019 helped force out longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir. In recent months, negotiations were under way for a return to the democratic transition.

As the plan for a new transition developed, Hemedti aligned himself more closely with civilian parties from a coalition, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), that shared power with the military between Bashir’s overthrow and the 2021 coup.

The protagonists in the power struggle are General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan (left), head of the army and leader of Sudan’s ruling council since 2019, and his deputy on the council, RSF leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (right), commonly known as Hemedti

Diplomats and analysts said this was part of a strategy by Hemedti to transform himself into a statesman. Both the FFC and Hemedti, who grew wealthy through gold mining and other ventures, stressed the need to sideline Islamist-leaning Bashir loyalists and veterans who had regained a foothold following the coup and have deep roots in the army.

Along with some pro-army rebel factions that benefited from a 2020 peace deal, the Bashir loyalists opposed the deal for a new transition.

The victor of the latest fighting is likely to be Sudan’s next president, with the loser facing exile, arrest or death. A long-running civil war or partition of the Arab and African country into rival fiefdoms are also possible.

Alex De Waal, a Sudan expert at Tufts University, wrote in a memo to colleagues this week that the conflict should be seen as ‘the first round of a civil war’.

‘Unless it is swiftly ended, the conflict will become a multi-level game with regional and some international actors pursuing their interests, using money, arms supplies and possibly their own troops or proxies,’ he wrote.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (R) of Saudi Arabia talking to General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan during a meeting in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in 2019

WHAT’S AT STAKE?

The popular uprising had raised hopes that Sudan and its population of 46million could emerge from decades of autocracy, internal conflict and economic isolation under Bashir.

The current fighting could not only destroy those hopes but destabilise a volatile region bordering the Sahel, the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.

Indeed, Sudan is Africa’s third-largest country by area and straddles the Nile River. It uneasily shares its waters with regional heavyweights Egypt and Ethiopia. Egypt relies on the Nile to support its population of over 100million, and Ethiopia is working on a massive upstream dam that has alarmed both Cairo and Khartoum.

Egypt has close ties to Sudan’s military, which it sees as an ally against Ethiopia. Cairo has reached out to both sides in Sudan to press for a ceasefire but is unlikely to stand by if the military faces defeat.

Sudanese army soldiers, loyal to army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, sit atop a tank in the Red Sea city of Port Sudan, on April 20

Sudan borders five additional countries: Libya, Chad, the Central African Republic, Eritrea and South Sudan, which seceded in 2011 and took 75 per cent of Khartoum’s oil resources with it. Nearly all are mired in their own internal conflicts, with various rebel groups operating along the porous borders.

‘What happens in Sudan will not stay in Sudan,’ said Alan Boswell of the International Crisis Group. ‘Chad and South Sudan look most immediately at risk of potential spillover. But the longer (the fighting) drags on the more likely it is we see major external intervention.’

The violence could also play into competition for influence in the region between Russia and the United States, and between regional powers who have courted different actors in Sudan.

WHAT’S THE ROLE OF INTERNATIONAL ACTORS?

Western powers, including the United States, had swung behind a transition towards democratic elections following Bashir’s overthrow. They suspended financial support following the coup, then backed the plan for a new transition and a civilian government.

Energy-rich powers Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have also sought to shape events in Sudan, seeing the transition away from Bashir’s rule as a way to roll back Islamist influence and bolster stability in the region.

Gulf states have pursued investments in sectors including agriculture, where Sudan holds vast potential, and ports on Sudan’s Red Sea coast.

Destroyed military vehicles are seen in southern Khartoum, Sudan, on Thursday

Russia has been seeking to build a naval base on the Red Sea, while several UAE companies have been signing up to invest, with one UAE consortium inking a preliminary deal to build and operate a port and another UAE-based airline agreeing with a Sudanese partner to create a new low-cost carrier based in Khartoum.

The Wagner Group, a Russian mercenary outfit with close ties to the Kremlin, has made inroads across Africa in recent years and has been operating in Sudan since 2017. The United State and the European Union have imposed sanctions on two Wagner-linked gold mining firms in Sudan accused of smuggling.

Burhan and Hemedti both developed close ties to Saudi Arabia after sending troops to participate in the Saudi-led operation in Yemen. Hemedti has struck up relations with other foreign powers including the UAE and Russia.

Egypt, itself ruled by military man President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi who overthrew his Islamist predecessor, has deep ties to Burhan and the army, and recently promoted a parallel track of political negotiations through parties with stronger links to the army and to Bashir’s former government.

WHAT ARE THE SCENARIOS?

International parties have called for humanitarian ceasefires and a return to dialogue, but there have been few signs of compromise from the warring factions or lulls in the fighting.

The army has branded the RSF a rebel force and demanded its dissolution, while Hemedti has called Burhan a criminal and blamed him for visiting destruction on the country.

Though Sudan’s army has superior resources including air power and an estimated 300,000 troops, the RSF expanded into a force of at least 100,000 troops that had been deployed across Khartoum and its neighbouring cities, as well as in other regions, raising the spectre of protracted conflict on top of a long-running economic crisis and existing, large-scale humanitarian needs.

The RSF can draw on support and tribal ties in the western region of Darfur, where it emerged from militias that fought alongside government forces to crush rebels in a brutal war that escalated after 2003.

People carry on their shoulders Othman Mohamed, a senior general loyal to army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, in the Red Sea city of Port Sudan, on April 20

CAN EXTERNAL POWERS DO ANYTHING TO STOP THE FIGHTING?

Sudan’s economic woes would seem to provide an opening for Western nations to use economic sanctions to pressure both sides to stand down.

But in Sudan, as in other resource-rich African nations, armed groups have long enriched themselves through the shadowy trade in rare minerals and other natural resources.

Dagalo, a one-time camel herder from Darfur, has vast livestock holdings and gold mining operations. He’s also believed to have been well-paid by Gulf countries for the RSF’s service in Yemen battling Iran-aligned rebels.

The military controls much of the economy, and can also count on businessmen in Khartoum and along the banks of the Nile who grew rich during al-Bashir’s long rule and who view the RSF as crude warriors from the hinterlands.

‘Control over political funds will be no less decisive than the battlefield,’ De Waal said. ‘(The military) will want to take control of gold mines and smuggling routes. The RSF will want to interrupt major transport arteries including the road from Port Sudan to Khartoum.’

Meanwhile, the sheer number of would-be mediators – including the US, the UN, the European Union, Egypt, Gulf countries, the African Union and the eight-nation eastern Africa bloc known as IGAD – could render any peace efforts more complicated than the war itself.

‘The external mediators risk becoming a traffic jam with no policeman,’ De Waal said.

Source: Read Full Article