“You can’t change a culture if you can’t name the things that need to change,” says Melissa Febos.

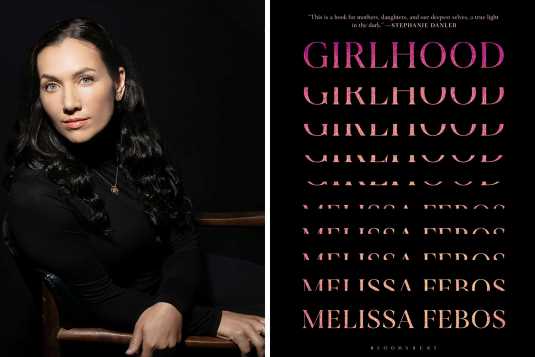

The author dives into that naming process with the release of her third book “Girlhood,” a literary collection of personal essays spring-loaded with social commentary. As the title suggests, Febos interrogates the experience of her own adolescence and gives language to traumatic minutiae of childhood interactions.

“I had thought that time was a closed case, like — oh, I talked about it in therapy, nothing happened to me that was a really serious trauma. It was just ordinary stuff,” she says. “And as I continued to write, I realized that was the very nucleus of what I was getting at — the very ordinary nature of the traumas of girlhood, and the ways that we as individuals and our culture teach us to dismiss them and think of them as not a big deal. But just because something is ordinary, it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t affect us profoundly and longitudinally.”

Febos moved to Iowa City last summer to teach as an associate professor in the University of Iowa’s nonfiction writing program. She spent the previous two decades in Brooklyn, where she lived when she published her first two books, “Whipsmart” and “Abandon Me.” “Girlhood” builds upon many of the ideas introduced in her earlier writing — her childhood in Cape Cod, her work as a dominatrix in the early Aughts, her experience as a queer woman — filtered through the lens of power and consent. She weaves in academic theory and pop culture references and exposes the problematic premises of popular teen comedies like “Revenge of the Nerds” and “Easy A”; the peeping Toms of James Ellroy novels (who was a peeping Tom himself) are horrific when placed next to Febos’ own experience with a stalker outside of her apartment window.

Related Gallery

Fall 2021 Trend: Maxi vs Mini

The framework around Febos’ personal stories are likely to serve as a mirror for many readers. As Febos began picking apart her childhood experiences, she had the urge to speak about them with other people. “Girlhood” includes results from a (admittedly self selecting) survey she offered to her network, which includes former and current sex workers.

“The more investigative journalistic aspects of [the book] were an outgrowth of my own desire to talk to other women about their experiences and say, hey, did you also experience this? And overwhelmingly the answer was yes,” she says. “So many of the women I talked to said, I’ve never even really thought about this, but my whole life has been a timeline punctuated by these kinds of experiences.”

Several essays explore various iterations of bullying by her female and male peers. When Febos was in her early 30s, she pulled out a diary entry from when she was 11 while visiting her childhood home, and read a description of an interaction with a neighbor whose bullying tactic included spitting on her. As a kid, she had written about the incident in a positive light.

“I was so unwilling to think of myself as a victim, that I was immediately reframing it in this very private way,” she says. The book touches on the idea of myths and the way even ancient stories have morphed over time, and what those stories reflect about the message society wanted to relay at the time. Similarly, Febos picks apart the narratives of her own experiences. “It’s been really transformative for me to go back and look at the ways that I was disempowered or victimized, and can also give back a kind of agency to my younger self by writing about it now, and rewriting that narrative into my adult experience.”

Febos reframes the idea of consent in the penultimate essay, “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself,” in which she uses the setting of a nonsexual “cuddle party” with strangers to explore what she describes as “empty consent.” (An idea that she also places in the context of sex work.)

“I had never talked about this [idea], and then when I talked to other women, we all experienced it, but there was no name for it. And I thought, of course — how could we change this if we don’t even have a word for it?” she says. “That’s my greatest hope for the book, that it gives people a language to name experiences that maybe they haven’t talked about. And that is how societal change happens. That’s how it starts.”

And while Febos writes about a deep-rooted proclivity toward choices to make the men around her comfortable, that inclination didn’t creep into her writing process. (And for others looking to follow suit, Febos next manuscript, recently completed, is a collection of nonfiction craft essays.)

“When I’m writing something, the only audience I imagine is the perfect audience; the person who most needs the thing that I’m writing — if I imagine anyone,” she says, before adding that many men and boys will relate to the same experiences she recounts in “Girlhood.”

“It’s not just girls who experience the conditioning of patriarchy; it’s really terrible for all of us. And there are plenty of boys and men who have experienced a lot of the really ordinary harms that I describe in the book,” she adds. “We all know about the worst-case scenario harms that come to women in a patriarchal culture, but this granular study of the ways that kind of conditioning informs our much smaller interactions, I really believe is the key to changing our culture. I think the book will appeal to men who are ready for that.”

More Book Coverage From the Eye:

WSJ Reporter Te-Ping Chen Makes Fiction Debut With ‘The Land of Big Numbers’

Nadia Owusu Explores Identity in ‘Aftershocks’

Bevy Smith Is Finally Exactly Where She Wants to Be

Source: Read Full Article