Higdon’s desire to make the sport accessible to all has made him a household name for all types of runners.

By Talya Minsberg

Hal Higdon is the 90-year-old internet king of running plans.

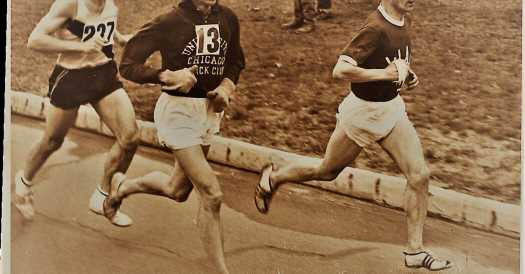

His brand has transcended his running career, a storied résumé that includes eight appearances at the U.S.A. Track & Field Olympic Trials and a personal best marathon time of 2:21:55.

Now, his name has become a brand, one that is synonymous with training plans for every type of runner, from beginners to Boston Marathoners.

“He’s all about the democratization of running,” his daughter, Laura Sandall, said. “He was all about making sure that anyone who wanted to get out and run could have a training program at their fingertips.”

At their fingertips, and at the top of Google search results. His free training plans have remained some of the most frequently used — a rarity in a world where most plans and coaches cater to runners who are willing to shell out hundreds of dollars for personalized schedules.

His unique blend of enthusiasm, a deep understanding of the sport and a big, supportive family have kept him top of mind for advanced and novice runners alike. But this wasn’t his plan, not exactly, according to Higdon and his family.

Higdon started running in high school, and began researching different ways to train for races while a student-athlete at Carleton College in the late 1940s. “I was a perky little freshman and sophomore who came up with training ideas of my own,” he said in a telephone interview. He honed his expertise as an elite runner both in the youth and master divisions, taking his family along with him for the ride.

Before races had water stations, his family would stand on the side of courses with cups of water. His children fondly remember spaghetti dinners before marathons. So, too, do they remember having marathon greats like Bill Rodgers stop by the family home for a meal or two.

In those days, Higdon made a living from freelance writing on a variety of subjects. But the through line remained working with athletes and writing for runners. It wasn’t until 1990, when a high school friend recruited him to design plans for Chicago Marathon runners, that he began crafting training plans for a larger audience.

“I don’t think I could have predicted my life at any point,” he said, speaking with the enthusiasm of someone who has never come down from a runner’s high. “I went with the flow. I had the intelligence I absorbed over decades of time, particularly for the kind of person who had no idea that he or she would become a runner.”

In 1993, he wrote “Marathon: The Ultimate Training Guide,” now in its fifth edition. He registered for a website in 1994, the same year Oprah Winfrey famously ran the Marine Corps Marathon. Running had hit a new mainstream fever pitch.

The Higdon family — three children and nine grandchildren — had been training for what was to come. Higdon began naming some of his family members: Jake (or, as Higdon called him, grandchild No. 5) and Jake’s father, David, helped get the website up to date. His granddaughter Sophie dove into Instagram. He started talking about his son Kevin’s role, before cutting himself off, worried he would not give everyone equal credit in the family business.

“Without leaving anybody out, all the family is involved,” he said. “It may as well be called the Hal Higdon team legacy.”

Jake estimated that about 2 million people used the training plans online every year. More recently, the site added two programs — TrainingPeaks and a RunwithHal app — that are subscription based. But, Jake added, it was a total non-starter to ever pull any programs off the website. More than 90 percent of runners only use the free plans.

“He has never been in it to make a ton of money,” he said. “Putting that barrier up would really fly in the face of trying to reach runners of all levels.”

And reach them he does. Sure, it’s a family affair. But each family member I spoke with was adamant about one thing: It’s all Hal talking to runners on Facebook and Twitter. He was an early social media adopter, his daughter Laura Sandall said, and the family set up a system to allow him to do what he does best.

“Grandpa Hal is the one that is still interacting with users,” said Kyle, a proud Higdon grandson. “He treats all the users the same way he’s treated me. It’s kind of like they are his grandchildren or children, his Hal Higdon running community. And I think that comes across in the way he answers each person’s questions and makes sure they are enjoying their training.”

Higdon has slowed his own pace recently (well, he did run seven marathons in seven months for his 70th birthday) and now opts for lower-impact workouts. He bikes two and a half miles to his favorite coffee shop, Al’s Supermarket, with his wife, Rose. That, he said, “is what has allowed me to live to a jolly old age.”

His family doesn’t argue that, but they say his online community has kept him engaged too.

“He gets up early every morning,” Sandall said. “I get alerts for his tweets.”

Post-Run Refuel: What We’re Consuming

READ

Jordan Gray is the U.S. record-holder in the women’s decathlon. But she and her peers are able to compete for Olympic berths only in the seven-event heptathlon. The decathlon is restricted to men.

That doesn’t sit well with many track athletes and fans. Gray’s movement — Let Women Decathlon — is nearing 20,000 petition signatures in favor of adding the women’s event to the Olympic Games in the name of gender equality in track and field, and it is gaining the support of Olympic icons who broke similar barriers decades ago.

WATCH

On June 26, long jumper Quanesha Burks qualified for her first Olympic Games. The 26-year-old jumped a personal best 6.96 meters to finish in third place.

Two days later, she uploaded what amounted to a “told you so” compilation to TikTok. The video cuts between different takes of the athlete saying the same thing. “I’m going to be an Olympian,” she said, “I’m going to the Olympics.”

The video ends with her standing at Hayward Field in Eugene, Ore., having done enough to make that happen.

LISTEN

Do the systems designed to catch cheaters really protect Olympic athletes? Lindsay Crouse, a writer and producer for The New York Times Opinion section, spoke with Mary Harris, the host of Slate’s “What’s Next” podcast about how athletes’ Olympic dreams can be hampered by controversial drug tests. Listen here.

One Last Rep

Post-Covid syndrome is still not well understood. So doctors are throwing the kitchen sink at helping these patients get better — and get back to sport.

They are adapting treatments used for other illnesses, and — with permission — drawing data from athletes’ personal fitness trackers, like Apple Watches, Garmins and Fitbits, which endurance athletes use to tell them how fast and far they went, Jen Miller writes.

Site Index

Site Information Navigation

Source: Read Full Article