After his liver transplant, Peter Karamihalis found himself repeating the same line: “It wasn’t because I was an alcoholic.”

The 62-year-old Paddington man had contracted Hepatitis C in his youth from transfusions for a blood disorder. The damage to his liver resulted in scarring and then a cancer diagnosis.

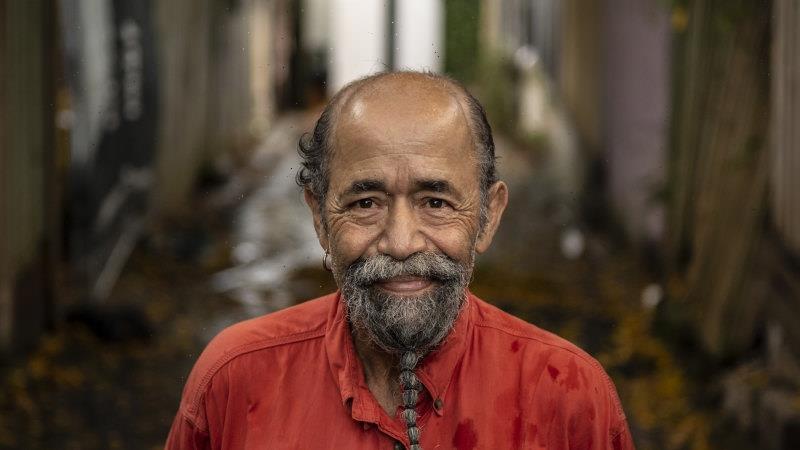

Peter Karamihalis, liver transplant recipient.Credit:Wolter Peeters

Treatment was tough. First, he had 20 per cent of his liver removed. Then his body rejected a liver transplant before a second successful attempt six years ago.

In the process he was jaundiced (turning yellow “like Homer Simpson”) and he is still lighter and weaker than he was before. But Mr Karamihalis still considers himself lucky when he remembers a decades-old friend he had made in hospital who was also receiving transfusions.

The friend followed him with diagnoses of hepatitis and, eventually, cancer.

“On the day I got my transplant he passed away from the same disease.”

Advocates are calling for greater public awareness of risk factors for liver cancer, amid rising instances of the condition which sees fewer than one in five survive for five years after diagnosis.

The most common form of liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is the fastest-growing cause of cancer deaths in Australia, a Deloitte Access Economics report commissioned by the Liver Foundation found.

It is estimated that 1466 people died of the condition during 2019-20, more than triple the deaths recorded in the 1980s.

Liver cancer develops following liver damage, caused by either chronic infection, or genetic and behavioural impacts. There were 2599 diagnoses during 2019-20, of which 73 per cent were in men.

Dr Simone Strasser, a liver disease expert at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, said there was “absolutely no question” incidents of the cancer are increasing, noting a shift away from cases like Mr Karamihalis’.

Unlike Peter Karamihalis, one in five people diagnosed with liver cancer do not survive within five years. Credit:Wolter Peeters

“As recently as five or 10 years ago, most cases were from viral hepatitis, but now a greater proportion are linked to lifestyle factors, particularly the obesity epidemic,” she said.

Other risk factors for liver cancer include type 2 diabetes, tobacco use and alcohol consumption.

Dr Strasser said people at higher risk should ask to be screened for liver cancer at their GP, noting too many cases are caught in an advanced stage.

Only 19 per cent of people live beyond five years after diagnosis, a rate which improves to 25 per cent with surgery and 75 per cent following a transplant.

While many associate liver damage with alcohol use, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is becoming an increasing challenge. Previous research has concluded the obesity-related condition now account for 30 per cent of all liver disease.

“Liver disease, in general, is associated with stigma … it’s not a sexy disease but it does affect a lot of people,” Dr Strasser said.

According to a 2020 review, instances of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease are predicted to rise 25 per cent in the next decade.

Richard Wylie, CEO of the Liver Foundation, said the disease was a “bogey man coming over the hill” for Australia’s healthcare system.

Factoring in health system costs and impacts on productivity and wellbeing, the Deloitte report concluded HCC costs the Australian economy $4.8 billion annually.

About $139.5 million was spent on HCC during the financial year, 50 per cent more than was spent on breast cancer per patient and more than double the per-patient expenditure on bowel cancer.

“Awareness in the community is not matching the impacts we’re seeing on a daily basis,” Mr Wylie said.

Start your day informed

Our Morning Edition newsletter is a curated guide to the most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Get it delivered to your inbox.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article