In the early 1980s, Gary Charles showed up for his final exam in a physical education class at Cheyney University with a dislocated elbow in a cast. He expected his instructor to look at the state of his right arm and give him a pass on the portion of the test where he would have to shoot baskets.

Instead, John Chaney told him there was nothing wrong with his left hand. Use that to shoot.

“He said, ‘Life ain’t going to be easy, either,’” said Charles, who became an influential youth basketball coach. “‘He was trying to get me ready for the real world.”

Chaney, the Hall of Fame basketball coach, died on Friday at age 89. He spent a decade at the eponymous-sounding Cheyney, the historically Black college outside Philadelphia, where he won a Division II national championship. He spent the next 24 years at Temple, which may as well have been named Chaney U. for the way he built the basketball program’s national profile in his image: as an uncompromising underdog.

Chaney’s raspy voice, dark undereye circles and perpetually loosened tie projected the image of someone who’d endured a long day at the office. (And typically he had — his practices ritually began at 5:30 in the morning.) His appearance also served as an apt reminder of his role as a fierce advocate for Black opportunity — jobs for coaches and education for players who grew up poor.

His death comes just months after that of John Thompson Jr., the former Georgetown coach, with whom Chaney teamed to protest N.C.A.A. regulations that made freshmen ineligible if they did not meet academic requirements and later made them pay their own way the first year. Basketball coaches who recruited players from inner cities in the late 1980s knew it would close off doors to a college education.

Thompson, a bear of a man who could use his 6-foot-10 frame to send a message, famously walked off the court before a game to protest. Chaney used his words: He called the regulations a “racist rule” enacted by “racist presidents.”

“If the history books could say one thing about any one of us it’s that we weren’t afraid to say what was on our minds and what we thought was wrong,” said Nolan Richardson, who became the second Black coach — after Thompson — to win a national championship at Arkansas. “We didn’t have to rehearse it.”

That came from shared experience. Richardson, who grew up in El Paso, Texas, couldn’t stay in the same hotel with his white teammates when his high school baseball team would play in towns like Odessa, Abilene and Midland in the late 1950s. When he played basketball at Texas-Western, he was left behind on the team’s trip to Louisiana State. Chaney was a high school star in Philadelphia, but none of the city’s colleges would recruit him so he went to Bethune-Cookman, a Black college in Daytona Beach, Fla., not far from where he was born. He starred there, but never got an opportunity to play in the N.B.A.

“I grew up with the fact that I wasn’t wanted; that never changed,” Richardson said. “I saw the same thing in John Thompson and in John Chaney.”

Chaney returned home to Philadelphia after playing and first coached at a middle school. By 1988, he had taken Temple to No. 1 in the country, at a time when the Owls were playing in McGonigle Hall, a 4,500-seat band box, and took on all comers, traveling to Duke, U.N.L.V., North Carolina, U.C.L.A. and whatever the powerful Big East had to offer. The coach, like his teams comprised largely of hometown talent from Philadelphia, embodied a city that easily wraps its arms around a gritty long shot.

It should come as little surprise that one of his favorite movies was the classic western “High Noon” — he identified with the sheriff who fights off a band of bandits alone.

Chaney would often stroll into the practice gym before dawn, a scarf around his neck, a winter cap on his head and a cup of coffee in his hand. If he had found himself in a buoyant mood on the drive over, he would listen to the news on the radio to find something to get agitated about. Inevitably, a pass would be delivered at somebody’s ankles or a jumper wouldn’t hit the rim and practice would come to a screeching halt.

Players would sit along the baseline and a lesson would unfold. It might be about a game he watched the night before, politics, or a recitation of a Langston Hughes poem.

“Sometimes you didn’t know where he was going,” said Dan Leibovitz, an associate Southeastern Conference commissioner who served as an assistant under Chaney for 10 years. “He’d tie into life, tie it into basketball. I’d hear a story 100 times and the 99th time I’d be all in.”

The metaphors and the stories would find a particular resonance in the homes of recruits who were raised by their grandparents, those who could nod knowingly about a college degree — more so than basketball — being a route out of poverty.

While visiting a recruit, Chaney would ask for a show of hands for anybody in the family who had attended college. Invariably, the only one would be the prospect. Chaney readily took players who had to sit out a year because they did not qualify academically under the rule he protested. Some were like Eddie Jones, who had a lengthy N.B.A. career, and others were like Ernie Pollard, who became a cop and runs a Police Athletic League basketball program in North Philadelphia. Another, Aaron McKie, is now Temple’s coach.

“If grandparents were in the home and they were strong with the recruit, you felt like it was over before it began,” Leibovitz said. “He’d be in the kitchen talking about the South or gumbo recipes. He promised that they’d be pushed and have a chance to graduate. He’d say, ‘I’m not going to stick a lollipop in your mouth, I’m going to coach you like a man.’”

Those old-school sensibilities, though, sometimes veered over the line.

Chaney made national news when he stormed into a news conference after Temple had narrowly lost to Massachusetts and charged at the opposing coach, John Calipari, shouting “I’ll kill you,” before he was restrained. Years later, he was suspended for sending a player into the game to rough up rival St. Joseph’s — leading to a St. Joseph’s player breaking an arm in a hard fall, which enraged Hawks Coach Phil Martelli.

A Philadelphia sportswriter brokered a meeting between the two coaches.

“It was almost like a mob movie — they emptied the restaurant and put the two of us behind a screened off portion,” said Martelli, now an assistant at Michigan. “We talked it out.”

Chaney, who had said publicly he was upset about hard screens by St. Joseph’s, told Martelli the real reason: A witness in a deposition about irregularities in Temple’s program said he had spoken to Martelli. What Chaney didn’t know was that in the deposition, the witness had also said that Martelli did not know anything.

“We had a real long conversation and that was that,” Martelli said. “It was very similar to Cal — ‘Oh, my god. They could never have reconnected.’”

Martelli said in the years after Chaney retired in 2006, they would occasionally run into each other — sometimes on the golf course — and that he marveled at Chaney’s gift for communicating. It was visible in the way Temple played — a hallmark zone defense and a principle of not turning the ball over — and in Chaney’s eyes, at rest tired and sorrowful, and then alive with energy.

“He had the passion and the fire of a preacher,” Martelli said. “He had such vivid descriptions of the only way young people are going to reach their ceiling is to raise the floor. When he spoke, your eyes went nowhere else in the room. He almost spoke through your skin and to your heart and to your mind.”

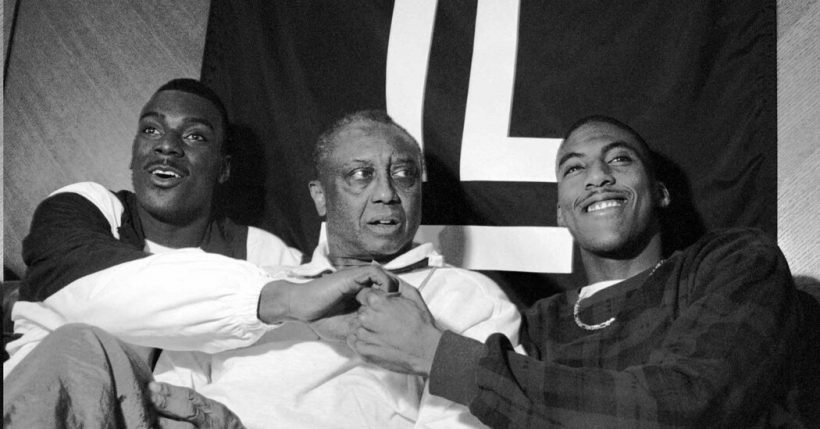

Chaney had a particularly captive audience among coaches at the Final Four. For years, he would be picked up at the airport by two of his closest friends in the business — Keith Johnson, who played for him at Cheyney, and Fang Mitchell, the longtime coach at Coppin State University who had helped him run coaching clinics. They would spend the long weekend talking basketball, just as they had years earlier when they helped Chaney run his basketball camp.

Johnson would sometimes marvel at his place there.

He moved from Philadelphia to New York after graduating from high school to do roofing work. Johnson returned home after a couple of years, and played basketball in summer leagues, holding his own against Gene Banks, then a star at Duke. A friend encouraged him to visit Cheyney to work out in front of Chaney.

The coach promised Johnson’s mother that he would get his degree, and so at age 22, Johnson enrolled. His mother eventually earned her high school diploma — at age 60.

“It was a life changer,” said Johnson, who spent 32 years as a college coach. “The only thing he told me is he wanted me to do for other people what he did for me.”

Source: Read Full Article